What you must learn about Continuity

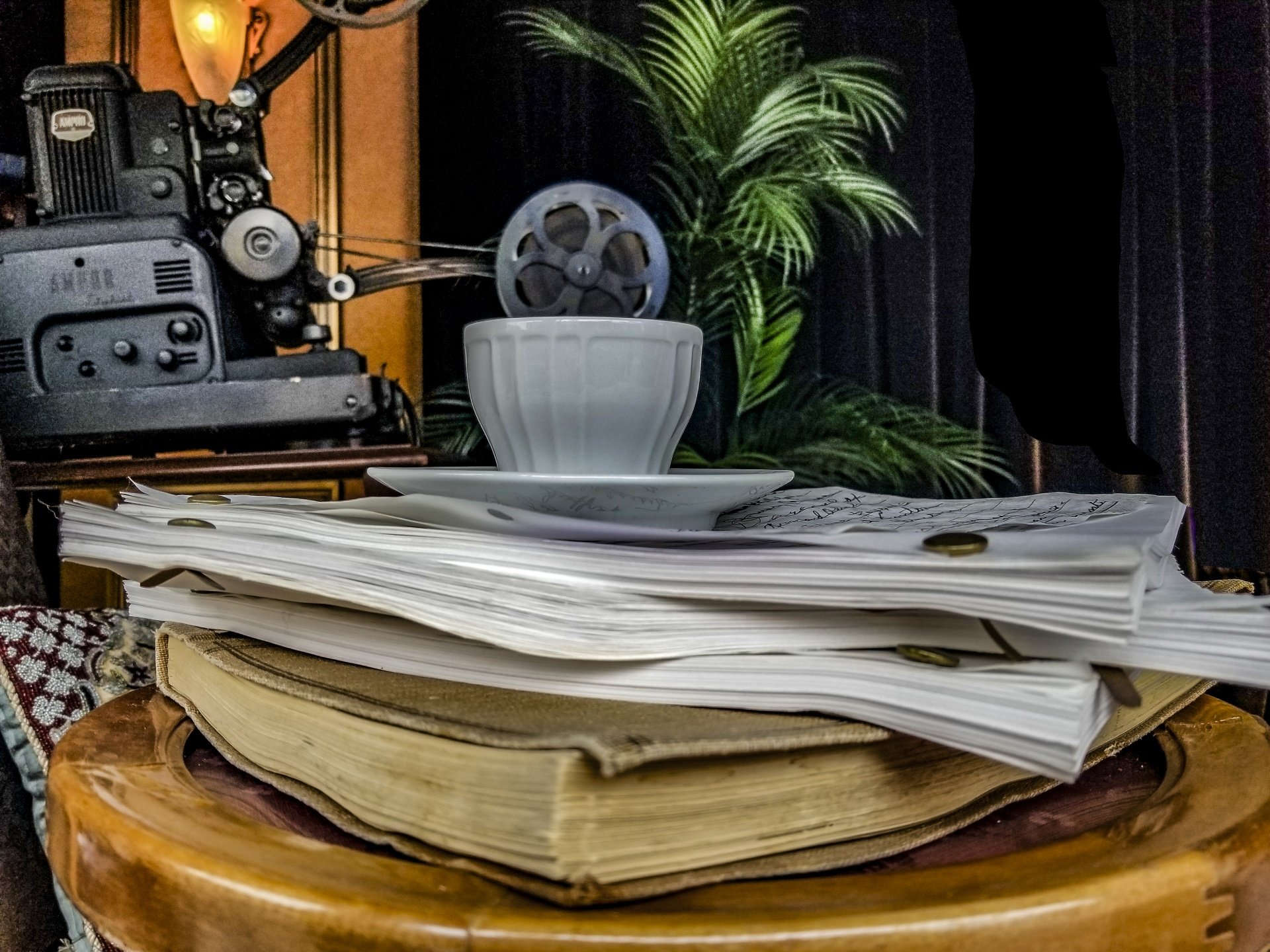

An expert guide with script supervisor and continuity professional, Michael Wray.

https://m.imdb.com/name/nm2067875/

Let’s start with a introduction and short bio about Michael Wray

I graduated from Macquarie University in 2007 with a Bachelor of Media in Film Production, & since then I’ve worked as a Script Supervisor on 35 features, 22 series & 120 shorts, working with different modes of filming & different film stock such as digital, stereoscopic, 16mm, 35mm & VR.

I’m also a huge collector of books on filmmaking, with a home library of around 1500 volumes.

Describe Continuity and it’s purpose for Film and TV production?

My job basically has two facets.

⭐ First up, I’m the official ‘note taker’ on set. I’m tracking everything from camera & sound notes (parallel to those respective departments doing the same), notes on each take from relevant departments for editing (Director’s comments, camera comments, art/costume/make up etc), plus basic information such as first turnover, lunch break, camera wrap. I’m also keeping track of coverage (eg, what scenes were filmed today, what scenes are incomplete etc) & writing continuity notes for the editor. Each day I compile my notes & reports to send to production.

⭐ The second area is being “ the editor’s eyes on set” - I’m watching internal continuity (if they grabbed the bag with their right hand or left hand, what time the clock on the wall should be on, making sure no Starbucks cups are in the shot - the fun stuff) & helping with keeping a secondary eye on coverage, making sure shots match, eye lines match, & making sure we haven’t missed anything.

The way I like to think about my job is the difference between a paramedic & a surgeon. The Editor is like a surgeon in a hospital - they’ll be doing the really hard work of spending long hours meticulously stitching the patient up. My job is like a paramedic - I’m “in the field”, & my role is to help get the patient (ie. the raw footage we’ve filmed) ready for the surgeon.

Please explain the phrase ‘Cross the Line’

Imagine a scene with two characters - Tim & Alice - sitting at a table talking to each other. They’re on opposite ends, & in the master shot, Tim is on the left side of the screen (facing the right) & Alice is on the right side of the screen (facing Tim towards the left). The “ line” is an invisible connection between the two characters. So, if you then move into close ups, when you film Tim the camera will be placed on his right shoulder, so he remains facing camera right, & Alice conversely will have the camera on her left shoulder (so she’s facing camera left).

This keeps the logic of the shots in synch.

So if you jump from the master shot to the close up of Tim, because in both shots he’s facing camera right ( & we established that Alice is opposite him), the edit is smooth & the audience can follow the scene easily (we know he’s talking to Alice). But, let’s say we film a close up on Alice where the camera is now on her left shoulder (so she’s facing camera right). We’ve now “crossed over” that invisible line, so if you show Tim’s close up (him facing camera right), but then this new close up of Alice (also facing camera right), the edit will be confusing because they won’t look like they’re talking to each other.

This is a simple example of course, but it forms a sound basis for the logic of coverage & continuity. As he says in the move Adaptation, “don’t think in terms of rules, think in terms of principles”, & “crossing the line” is a perfect example of this. It’s not a hard-fast rule (nothing is), but the purpose of it - the principle - should be making the edit smooth & making sure the audience can follow the logic of the scene.

Where does Continuity fit within the hierarchy of film production roles?

We’re a solo department, but we sit by the monitor with the Director & (in a perfect world) liaise with the cinematographer, sound, art, make up, costume, producers - everyone.

I tend to have a philosophy of “laying my cards on the table”. I don’t like keeping information from people (nor do I want people to do likewise), so I never have a problem showing my photos to anyone, nor do I mind anyone getting my reports & notes (if needed & relevant, of course).

What is the best way to monitor and control continuity? Are there any industry standard apps, tools or guides that professionals use?

The last few jobs I’ve been doing I’ve been using a software developed by a person named Peter Skarratt, but in the past I’ve also used software called ScriptE (which is popular), or even simply my own spreadsheet on Microsoft Word. There isn’t a “one size fits all” standard app or software.

Like anything in filmmaking, everything you do changes depending on factors like country, budget, culture, time period, equipment etc (even something seemingly tiny such as using a slate or not using a slate will have an impact on the culture of the set & post workflow), & I find that I’m adapting constantly depending on the needs of that particular job. Shooting in 35mm film will require some differences in terms of paperwork than shooting in VR (which is completely different to anything else).

In a basic sense it’s a combination of four things - photos, notes, memory, other departments. And like riding a bike (foot goes here, hand goes there, balance here) you have to develop your muscle-memory so as to know when to take a photo, what notes to write, what you can commit to short term memory, & what things you rely on (or relay to) other departments. In fact 90% of the time I do stand on the shoulders of make up, wardrobe & art, & without their tireless efforts my job would be a million times harder.

I think it also boils down to having a good system. If it’s at the end of the day, 2 minutes to wrap (lest we risk overtime) & an actor suddenly yells “When we did this this morning, were my glasses in my left or right hand?” you need to be able to answer quickly. If you don’t have it in your short term memory, then you need to check notes. If it’s not there, you need to check photos (or something else). You don’t have time to potter about too much. But if you have a good system for storing information (good notes, photos well documented etc) then that’s 95% of it.

What are 3 common errors filmmakers make during shooting?

This mostly applies to first-time directors, but a big one is to learn to trust your crew.

⭐ The reality is that your average crew member has clocked a million more hours on sets that your average Director, so even though the Director is in charge, they should trust the expertise of the cinematographer, sound department, wardrobe etc. And Director’s need to respect the crew. You might want to get three more takes of this close up because you’re in love with the performance, but remember that some poor bugger will be staying back an hour to take down lights after wrap. Trust & respect them, & they’ll work hard & help you fulfill your vision.

⭐ Secondly, & building on this, is that if you’re a Director, you don’t need to know everything. Obviously the more you know about technical elements of filmmaking the better, but some first time Directors get the feeling that they need to understand lenses & different microphones etc when they don’t (& I know of some people who have postponed Directing out of fear that they don’t know enough of this stuff). Your job as Director is to simply be the conduit for the vision of the film, & communicate this to the crew. You don’t need to know lenses & different cameras - all the Director needs to do is say to their cinematographer “Did you see this movie? Ok, you know the bit when the guy walks into the pub, & the camera swirls behind him like that? I’m think that same type of shot for here” & the cinematographer will go “Yep! I know what you want” & he’ll turn to his team & say “Put a 50mm on, put it in a steadicam etc”

⭐ And lastly, remember you can do a lot with editing. Even before the days of digital, when filmmaking was a lot less malleable than it is now, with a bit of imagination & skill you could do a lot with simply a shot-reverse shot of two people talking. So sometimes directors will waste a lot of time trying to get the “perfect take”, when in reality they have two takes that are both “50% good” - combine them & you get 100%.

It’s a lot like cooking. The recipe might call for three onions, but the chef might only have two. But with the right spices & combination of ingredients, a skilled chef can make a meal that feels like you have three onions - & the diner will be none-the- wiser.

What are 3 tips to best monitor continuity during production

⭐ Firstly, I spoke above about having a good system in place for storing & retrieving notes & photos. An adjunct to that is “learn to trust your system”. If you say to an actor that the bag was in their left hand but they insist if was in their right hand, if your system clearly states “left hand”, then stick by your guns & trust that system (and if your wrong, then own it. We’re all human).

⭐ A second tip is to learn to adapt. Most people think our job is to be a detail obsessive (ok, sometimes yes), but you also learn over time what’s important & what’s not important. Continuity depends a lot on factors such as coverage (what are we actually seeing on screen), blocking (what is the actor going to do), & the director’s vision & intent. Sometimes you need to stick to your guns & say “it has to be in the left hand!”, but other times you can say “it doesn’t matter” because you know that on one take the bag was in their left, another take it was in their right, & this shot we’re about to do is framed above their hands in a close up, so we won’t see it anyway. No use causing an argument with an actor who “insists on holding it in their right”.

And sometimes you have to realise that time & budget are going to get in the way. As Lorne Michaels, who runs Saturday Night Live says, “The show doesn’t go on the air because it’s good. It goes on the air because it’s 11:30 on a Saturday night”. You could sit there for hours arguing over “left hand or right hand”, but the Producers & AD will be sitting there tapping their watches. The need to go home & sleep may outweigh the need for “perfect continuity” on a tiny close up.

⭐ Thirdly, I think it’s important to remember “A stitch in time saves nine”. Movie sets are well run (& expensive) machines, & you should always try & solve a problem early & secretly. There will be moments where you’ll genuinely get to be the “hero” (on take three you’ll go “They should have their hat on!” & you’ll get a pat on the back for spotting it), but best case scenario you should check that issue with the hat much earlier with wardrobe, so we don’t waste three takes. And sometimes you need to let other departments take credit for something you fixed. It’s like playing basketball…

Sometimes you’ll make an amazing shot & score a bunch of points (& those moments will happen) but sometimes for the greater good of the game you need to pass the ball three times & let someone else make the winning shot.

Photos thanks to Sie Kits (ChristMess, A Heath Davis Film), IMBD and creative commons